“The Last Lines of Henry Thoreau and Yeats’ Ring-Stained Copy of Walden”

For the month of July, here on Trasna, we will be highlighting some of the literary and artistic events cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early July of each year, The Henry David Thoreau Society holds its Annual Gathering. This year’s theme was “DIVERSITY.” While an ever-important subject, it could hardly have proven more timely. Ibram X. Kendi, a leading scholar of race and discriminatory policy in America, was to be the Keynote Speaker.

Trasna editor Christine O’Connor was scheduled to deliver a paper on Thoreau and the anti-Irish views of the 19th century. The following essay, however, is about what ties us together, the commonality of our experiences, and the impact writers can have on each other.

Explored is the literary connection between Thoreau and Irish poet W.B. Yeats. Theirs is a reminder that whether walking the shores of Lough Gill or Walden Pond, we often travel the same path.

“The Last Lines of Henry Thoreau and Yeats’ Ring-Stained Copy of Walden”

by Christine O’Connor

“Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in.” It’s on a Thoreau tee-shirt I was folding as I packed for a trip to Ireland. I was leaving in less than a week, and there was still much to do. Tugging against these demands was a first-ever exhibit on the journals of Henry David Thoreau. It opened that summer in New York, and now in late autumn, its final days were winding down in nearby Concord, Massachusetts. Henry’s bearded face stared up at me. But where does all the time go? I replied.

It is less than a 30-minute drive along a beautiful, leafy road from my home in Lowell to Concord, but there is a distance between these communities that runs much deeper. In the mid-19th century, Lowell was a leading industrial center and a home to some of the largest numbers of Irish immigrants. They dug canals, built mills, and laid miles of railroads. Concord, by contrast, was a historic, affluent, farming community of multi-generational New Englanders. In the mid-19th century, it was also home to some of America’s greatest writers and philosophers.

Throughout the Northeast, tensions between Protestant Yankees and incoming Irish Catholics resulted in a rise of nationalism and anti-immigration sentiment. Whether Thoreau shared these feelings has been the source of much scholarship. Regardless, there is an undeniable connection between Thoreau and Concord’s Irish. At Walden they were his neighbors, living much like himself, on the edges of society; there were the Riordans, Irish immigrants who came to live with Thoreau’s family on his invitation; and, then there is his cabin at Walden, built from the wood of a so-called Irish shanty that Henry purchased from James Collins.

Outside the Concord Museum, a banner fluttered in the cool November air: “This Ever New Self, Thoreau and His Journals.” Inside stood his green desk, worn bare in places; his spyglass and flute; his T-square and compass; his copy of the Bhagavad-Gítá; the lock from the cell in which he spent a night in jail; and even the pen “brother Henry last wrote with” as his sister Sophia recorded on its tag.

But, as noted on the banner, his journals were the real attraction. He had given many of them names, like Big Red his earliest surviving volume; the Indian Books dedicated to his study and admiration of Native Americans; the Canada Notebook; or the Long Book which traveled with him and his brother John for a week on Concord and Merrimack. Now it rested in the display case opened to the start of what became the Saturday chapter in the book named for that trip.

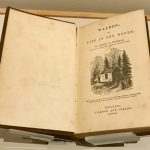

There were of course the journals from his two years, two months, and two days at Walden Pond. It was this writing, more than any other, that stands as his most influential work. It was rewritten and revised over a period of several years. In the end there were over a thousand manuscript pages and seven major drafts, until on August 9th, 1854 he wrote in his journal: “Walden published.” The title page had a sketch of his cabin that his sister Sophia drew.

But it was the journal without a name that left the greatest impression on me. It was his last journal. On the top half of a page are its final words written after a violent rain storm: “I can tell within the smallest fraction of a degree from what quarter the rain came. All this is perfectly distinct to an observant eye – & yet could easily pass unnoticed by most.” Looking at the thin, slanted handwriting and the blank space that followed I thought of Henry, sick with tuberculous, looking out his window; on his lap, the same journal that was now under glass; his pen resting lightly in that space between his thumb and forefinger; and of his gaze, following the splatter of each drop hitting the ground. Months later in May of 1862, Thoreau died of consumption at age 44.

In the days that followed, the experience of that exhibit traveled with me as much as the neatly folded items in my suitcase, and soon after arriving in Dublin I learned of another exhibit. On display at the National Library of Ireland were drafts of W.B. Yeats’ poems, plays, and even some automatic writing. There were his personal belongings: spectacles, a passport, a deck of tarot cards, and his Medal from the Irish Academy of Letters.

But it was in the section dedicated to his “Early Years,” that a surprise awaited me. Resting behind the plexiglass was an opened copy of Walden. In the upper right-hand corner, Yeats had signed his name and entered the date: April 2nd, 1886. By that time Walden had gone through several printings, and Sophia’s sketch of the cabin was no longer included.

When Yeats was a child, his father read Walden to him. The book left a lasting impression. Because of this author from America, Yeats dreamed of building a cabin on the uninhabited island of Innisfree. It is the smallest of the 20 islands of Lough Gill, a lake in County Sligo. Having just arrived in Dublin, I was delighted with thoughts of a young Yeats crossing the ancient waters of Lough Gill, but thinking of the glacial kettle hole not far from my own home.

It wouldn’t be until years later though, that Walden and Yeats’ dreams of living alone in the “bee-loud glade,” found expression. While he was walking along a busy street in London, the sound of water from a fountain reminded Yeats of the water lapping on the shores of Innisfree, and of his earlier Thoreauvian dreams. “I still had the ambition formed in Sligo in my teens, of living in imitation of Thoreau on Innisfree.” Within a few days he began to work on a poem that was to become one of his most popular, The Lake Isle of Innisfree: “I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree, / And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles/ made.”

Lingering before Yeats’ opened copy of Walden, I noticed a faint, circular impression left by a glass that must have once rested on it. Somehow this ring-stain struck me. It was an ordinary, yet intimate detail, likely left by Yeats himself. If Lake Isle of Innisfree made Yeats a literary heir to Thoreau, the ring-stain was a reminder that Yeats, like me, was once a reader of Thoreau.

Outside the National Library the sky was gray and heavy.

“Looks like rain,” I said to one of the library staff at the door.

“Maybe a shower,” she replied.

In Ireland there is no shortage of words for days of meteorological outbursts. It’s a country that recognizes the difference between a soft day and a rotten day; between a mist and a drizzle (a mizzle if you’re wondering). We can debate (and we do) whether Henry was fond of 19th century Irish immigrants, but he clearly would have admired the attention they and their forbearers gave to rain. After all, the Irish distinguish between such things not just because they can; but, because they understand the difference.

Sure enough, as I got back to the car the day turned wet. A faint bit of sunlight stretched across the M4 as I headed west to family in Galway. The woman at the exhibit was right, it was more of a shower, as a hundred little drumbeats battered hard against the roof. I thought of how it was the rain that delayed the start of Henry’s beloved canoe trip with his brother John; and how the rain kept him under the “Irishman’s roof” as he unsuccessfully philosophized with John and Mary Field in the climax of Walden. But, the rain washes us anew; it is timeless and universal. It can even give fresh perspective to old questions. When he saw an Irish woman sitting bare-headed in the icy rain, knitting, it evidenced to Thoreau how “close to the earth” the Irish lived. For Thoreau, there could be no higher compliment.

As the RTÉ News played in the car, my thoughts drifted back to Henry, sitting in his chair listening to a rainstorm knowing his last days were approaching. I thought too of Yeats listening to the movement of water from a city fountain and hearing Henry’s inspiring call to Nature. When the shower let up, an even sweeter sound came to me: brother Henry’s feathered, steel-tip pen scratching those last lines across the page.

Christine O’Connor is completing a collection of literary-themed essays, as well as a memoir on her grandmother and the Titanic. Much of her writing has connections to Ireland, where she is an active member of its writing community. Christine still has extensive family in Sligo and the west of Ireland, and enjoys frequent visits on both sides of the Atlantic. This summer she was to present a paper at the Annual Gathering of the Thoreau Society on Thoreau and the Irish Question. She is one of three editors of Trasna, which features new writing from Ireland. She holds an M.A. in American Studies from Boston College, a J.D. from Suffolk University, and serves as the City Solicitor for Lowell, Massachusetts.

Photos by Christine O’Connor. Above she is with family member, Teresa Toolan, at the grave of Yeats in Drumcliffe, Sligo

6 Responses to “The Last Lines of Henry Thoreau and Yeats’ Ring-Stained Copy of Walden”

Jeannie Judge says:July 3, 2020 at 9:38 pmWhat a treat to see this essay with photos in Trasna! I really enjoyed the point that Yeats, like you, was a reader of Thoreau. It is an impressive piece of writing, Chris. Thanks for posting it. I’m sorry that you missed your trip to Ireland and chance to meet Ibram X Kendi.

Margaret O’Brien says:July 5, 2020 at 10:21 amThank you Chris for this essay linking those two great writers and thinkers across (Trasna) the Atlantic. Your own personal reflections add special depth to the writing, completing a triangle it seems to me.

Eileen Acheson says:July 5, 2020 at 4:49 pmChristine I came to your essay today – a quiet Sunday which held soft rain.

I will hold the images created by you beyond time.

Such an appreciation you possess for the writers that speak to your heart and what an ability to link ( or as my grandfather would say “to trace “.)

The connections continue over and back accross the Wild Atlantic and between the generations of writers .

Long may you travel to us be it by plane or zoom.Mary McGrath says:July 5, 2020 at 6:55 pmGorgeous piece of writing. It never occurred to me about the Irish and the rain until I read it in your piece. Really interesting piece, well done. And sure it can’t rain all the time even if it does try its best to here.

Lindy says:July 6, 2020 at 9:59 amWhat a nice start to my morning. A lovely essay, and thoughts that will stick with me. Thanks for sharing.

Steve O’Connor says:July 8, 2020 at 6:48 amWell done. I hope you can deliver the essay in Concord next year.