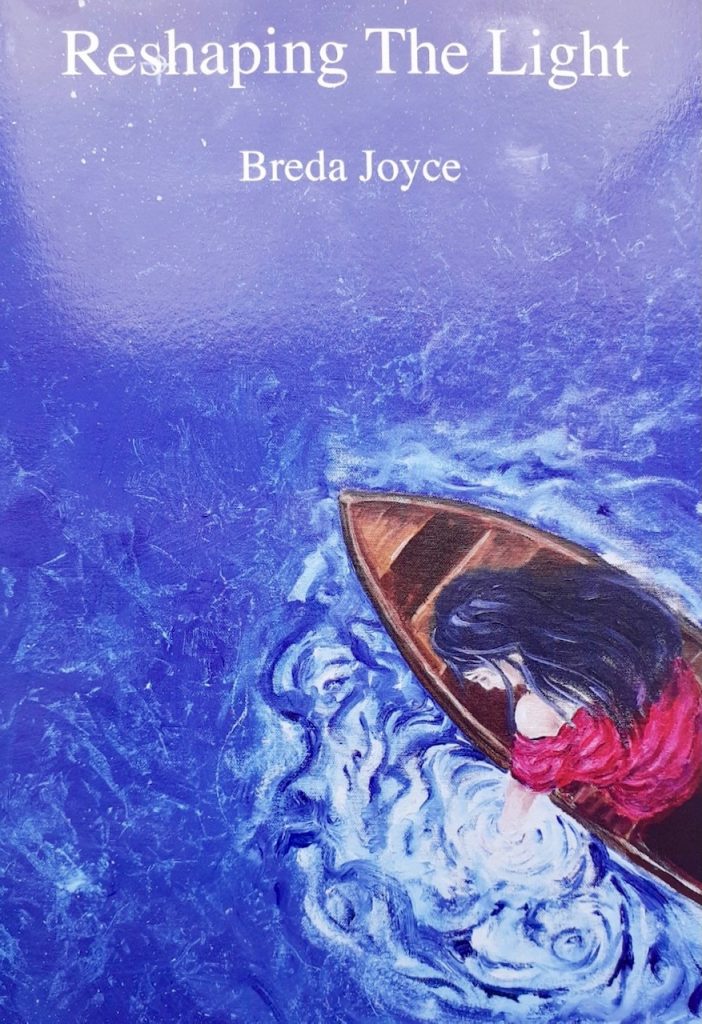

“Reshaping the Light” by Breda Joyce

Autumn is the season that embraces reflection: thoughtful persons give thanks for their harvest even as they mourn the [human] losses that befell them during the time past. In the poems she reads for Trasna, works from her newly published collection Reshaping the Light, Irish writer Breda Joyce voices the depth and wisdom of her autumnal vision. She speaks lovingly of the sorrow that often goes unknown: in “Lucia” the loss of the daughter who died “without having taken one breath”; and she acknowledges the pain of the mother whose hospitalized son is isolated. She touchingly relives her experience of the shell-shocked veteran whose hold on the world was marginal. In an insightful view, she describes the funeral of her father whose “polished shoes” led his procession out of the church. (J. Judge)

Lucia

When clocks go back, I think of you where darkness sits,

where apples quickly rot and are ripe with death

and fall on barren land in a silent earth.

Your name’s before me when the candle’s lit.

I never imagined someone so small, so intimate,

would bleed out without having taken one breath.

I was Demeter pleading with Hades to rebirth

the dreams I had for you in your Moses basket.

In November along the gable wall colour crawls

and tendrils weave a tapestry of tangerine.

You glide, and fallen leaves become your wings.

We planted a tree to remember you that Fall,

named it Liquidambar. It would grow in the spaces between

your sisters, measuring their years in the circles of your rings.

Visiting Rites

for my mother

I saw the tears in her eyes when she asked the nurse

about her little boy and I squeezed my mother’s fingers

in the ward with the bad smell.

My brother stood red cheeked and crying in the corner,

hands raised above the gate of his cot.

My mother took an orange from a brown paper bag,

held its coolness against his raging cheek,

then peeled the hissing skin and sprayed

the air with a citrus mist.

She offered him a segment and my brother

squeezed its sweetness between his tiny teeth.

When visiting time was up, my mother unclasped

sticky arms from around her neck, laid down

her little boy among the oranges and from his cot

he threw each one out between the bars.

Now it is my mother who stands in isolation inside a gate,

and from her doorstep looks out across a vacant space.

My brother leans across to place a bag of oranges

on the other side.

The Major

Major Livingston, his name,

a man who battled demons from the trenches

of our small western town. As children

we fell in behind him, foot soldiers

who sniggered at his muttered commands.

The Major searched the sky for shrapnel,

right hand raised to shield his eyes

against what might come.

We imitated his salute and stalked him

along razor wired ditches to the Demesne.

Here he gave orders to prepare,

to be ready to breach enemy lines.

We saw spitfires and fighter planes

on the horizon behind Knockma,

ducked down to save our lives.

My father told us he had shell-shock,

but we did not understand. When he asked

for The London Times in our grocery shop –

a special daily order for the Major –

he intoned our enemy’s vowels.

For Sunday Mass, he dressed well:

tweed jacket, Crombie coat and trilby hat.

But when the priest droned on too long,

the Major’s command reached the altar:

wrap it up now, wrap it up, wrap it up…

Later, I saw him on the bridge below our town,

tweed jacket flapping, trilby askew.

Almost did not recognise him. He raised

his large white handkerchief, heaving and sighing.

And it was then I knew.

Funeral Shoes

Saturday nights, my father rolled up

his white shirt sleeves, laid out an old newspaper,

a tin of Kiwi shoe polish and two soft brushes.

I’d hand him the smaller one to dab against the wax,

inhale the scent of carnauba,

then present him with the polishing brush

and watch his bulging veins buff up a shine

from matt to sheen to mirrored black.

Lots of elbow grease, he’d wink at me

and polish briskly in both directions.

His funeral shoes, my father called them,

always ready by the front door.

You never know when you might have to go

and pay your respects. We never know who’s next.

When he died, I was still young.

His brother in sandals, home from the missions

needed shoes to officiate my father’s funeral mass.

As he blessed the coffin, wafts of melting wax

brought me back to being my father’s acolyte.

I watched his own shoes lead his coffin

out the front door of the church, knew

they were taking him where he had to go.

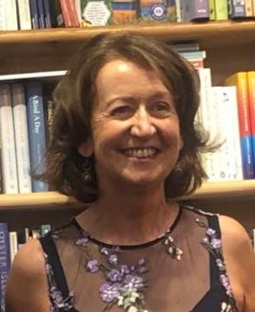

Breda Joyce grew up in Co. Galway and taught at second-level in Kenya and in Cahir, Co. Tipperary. On retiring from teaching, Breda studied creative writing in UCC where she won her first poetry prize and graduated with an MA in 2020. Her work has been twice shortlisted for the Anthony Cronin and the Over the Edge Awards, for the Fish Lockdown prize 2020, the Francis Ledwidge award 2021 and the Desmond O’ Grady prize 2021. Her short collections have been highly commended in the Fool for Poetry Chapbook competition 2019 and 2020. Her poetry appears in various publications, anthologies and literary journals, the most recent being Poems for Pandemia and The Best New British and Irish Poets Anthology 2019-2021. ‘Reshaping the Light’ published by Chaffinch Press is her first poetry collection and can be purchased through the following outlets: Chaffinch Press; Breda Joyce; Tudor Artisan Hub, Carrick-on-Suir; Charlie Byrne’s Galway; The Book Centre, Waterford.

2 Responses to “Reshaping the Light” by Breda Joyce

Steve O’Connor says:October 23, 2021 at 8:04 amBeautiful lines, Brida. Your reading of them gives them even greater resonance.

Michael O’Brien says:November 14, 2021 at 5:29 amSuch simplicity Breda yet so poignant; reflecting the love between you and your Dad .

Enjoyed listening to the Queen of Cahir this morning on Sunday Miscellany.

I will hopefully be getting my copy of “Reshaping the Light “ at Tudor Artisan Hub here in Carrick tomorrow.😊