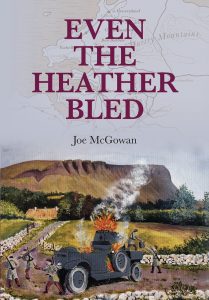

“Even the Heather Bled” by Joe McGowan

On the morning of Wednesday September 20th 1922 – the closing months of the Irish Civil War – soldiers of the Freestate army shot dead six anti-Treaty Volunteers atop Sligo’s Benbulben Mountain. How did it come about? That Irishmen, former comrades, after together winning a bloody war against the British Empire, killed fellow Irishmen on a lonely Sligo hillside with a ferocity unseen since the Black and Tan times?

Richly illustrated with images of the period, Even the Heather Bled sets out to answer this question. To explain the historical context the story begins with the invasion by Strongbow’s forces in August 1170. It tracks Ireland’s crucible of conquest, colonisation and survival from that Norman invasion to the birth pains of the Irish Nation in the 20th century: Penal Times, the Great Hunger of Black ’47, Davitt and the Land League, the Celtic Renaissance, the Easter Rising, War of Independence, Civil War, and Sligo’s part in that journey, are all detailed in McGowan’s latest book.

from EVEN THE HEATHER BLED

“A sense of foreboding hung heavy in the air that heinous Wednesday morning of September 20th 1922. Black plumes of vapour one after another had rolled sullenly across the face of Benbulben all morning; there was an ominous calm. Day had dawned bleak and wet – as had many another – but this one somehow was different; it was unnaturally still people remembered afterwards, both hill and valley shrouded eerily in mist and fog. For days the sodden clouds had obstinately hidden the hills and valleys, blanketed the boglands, swelled the little silver streams to self important wee prattling rivers. It saturated the few ill-clad farmers clamping turf on the Gleann gCailleach and Cloonerco bogs. By contrast the heather’s vivid purple, its colours presciently funereal, but nevertheless joyful now in the rain, adorned hill and bog, lit the turf-brown shadows, lightened the gloom. It was mid harvest and despite bad weather the crops: turf, hay, potatoes, all must be saved. There was no alternative, no assistance from the State, and meagre income from subsistence holdings. In the small farms of Grange, Ballintrillick, Ballymote or Easkey shortening days and waning sun lent urgency to their preparations. Men hurried about digging potatoes, harvesting grain crops, laying foundations for the hayricks, cutting rushes to thatch them, twisting straw ropes on starry moonlit nights to secure them. Sure there was a Civil War going on, and the sounds of conflict, like distant thunder, could sometimes be heard from afar. Just yesterday an armoured car, under hot pursuit, had been destroyed by armed men over there at Carnamadow, the occupants narrowly escaping death or capture. Troop movements on the Sligo to Bundoran road were worrying; only recently there was a pitched battle at Rahelly, but the harvesting must go on. On farms where the men of the house were on the run – sleeping in safe houses, dugouts and mountain caves – neighbours pitched in to help. About noon, on this darkest of days, the sound of artillery, machine gun and rifle fire reached a crescendo, the clamour of war seeming to come from the direction of Clough in North Sligo. Men and women looked up from their work, blessed themselves and breathed a prayer, for surely men were going to die on this day that blind rage shattered the serenity of Benbulben’s peaks and valleys; when Irishman fought and killed brother Irishman with a bitterness and cruelty unsurpassed even in the darkest days of the Black and Tan terror.

“Come out Ye Black and Tans; Come and Fight Us Man to Man.”

How did it come about then? That good men could plumb such depths? To where should we retrace our steps to discover how Ireland’s centuries old fight for freedom could lead to such an impasse; to the cream of Ireland’s manhood dying at the muzzle of former comrade’s rifle on a lonely Sligo hillside? Should we go to the faithless – or hapless perhaps, depending on which version you believe – Dearbhla’s ill-fated elopement with the swaggering Diarmuid Mac Murchadha in the twelfth century: that fateful episode that had its tragic outcome in the introduction of the Norman hordes to Ireland!2 To the 16th century Battle of the Yellow Ford maybe; or perhaps to the Battle of Kinsale that spelled the end of the old Gaelic order in Ireland? Defeats we had many: Battle of the Boyne, Rebellion of 1641; the pitch-capped Wexford rebels of 1798. Of victories we had a few: Battle of the Yellow Ford, Battle of the Curlews, Battle of Benburb, War of Independence and more: ‘I call to your mind Red Hugh, And the castle’s broken word; I call to your mind O’Neill, And the fight at the Yellow Ford: –And the ships afloat on the main, Bearing O’Donnell to Spain, For the flame of his quick and leaping soul To be quenched in a venomed bowl: –And the shore by the Swilly’s shadows, And the Earls pushed out through the foam, And O’Neill in his grave-clothes lying, With the wish of his heart in Ireland, And his body cold in Rome….’ (Stephen Gwynne). Let us look then at the torturous crucible that forged a modern Ireland.

Joe Mc Gowan is a native of Mullaghmore, Co. Sligo, Ireland. His short stories, cameos of Irish life both past and present, feature frequently on national programmes such as RTE1s Sunday Miscellany. He lectures widely on history and heritage topics and is the author of several books: In the Shadow of Benbulben; Inishmurray: Island Voices; Constance Markievicz:The People’s Countess; Inishmurray: Gale, Stone and Fire; Sligo: Land of Destiny; Echoes of a Savage Land; The Hidden People; Sligo Folk Tales and now Even the Heather Bled

2 Responses to “Even the Heather Bled” by Joe McGowan

Jeannie Sargent Judge says:September 28, 2021 at 3:57 pmA must read!

Steve O’Connor says:October 6, 2021 at 6:37 amThe reader gets the feeling that in Ireland, as Faulkner once said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” It seems to hang over the landscape like the fog and “sodden clouds” that Joe McGowan describes over Sligo that morning. Well done!